I am too pretty for Ugly Laws - Lateef McLeod

by Jenny Kwon (they/she)

I began reading Disability Visibility in the summer after seeing Alice Wong's Twitter announcement that the anthology had finally been published. I always look for ways I can better learn about disability justice, and I consider myself incredibly lucky to live in an era where I can learn about perspectives from social media platforms like Twitter, a platform that disability activists have used for years now to connect and mobilize. However, reading so many different perspectives from a single disability-centered anthology is something I had yet to do. I realized, to a lesser degree than Alice and all the writers who contributed to the anthology, that Disability Visibility was revolutionary in putting disabled voices and dreams into modern mainstream media, and I was incredibly excited to take a deep dive.

In the gallery below (in the form of an accesible carousel), I have illustrated my interpretation of six stories that touched me and impacted my view of what constitutes disability justice and what is needed to create a kinder and more accessible world. These stories include: "Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time" by Ellen Samuels, "The Beauty of Spaces Created for and by Disabled People" by s.e. smith, "How to Make a Paper Crane from Rage" by Elsa Sjunneson, "Nurturing Black Disabled Joy" by Keah Brown, "I am too pretty for Ugly Laws" (a poem by Lateef McLeod embedded in the story "Gaining Power through Communication Access"), and "I'm Tired of Chasing a Cure" by Liz Moore.

Gallery trigger warnings: motifs of anxiety and 'curing' disability

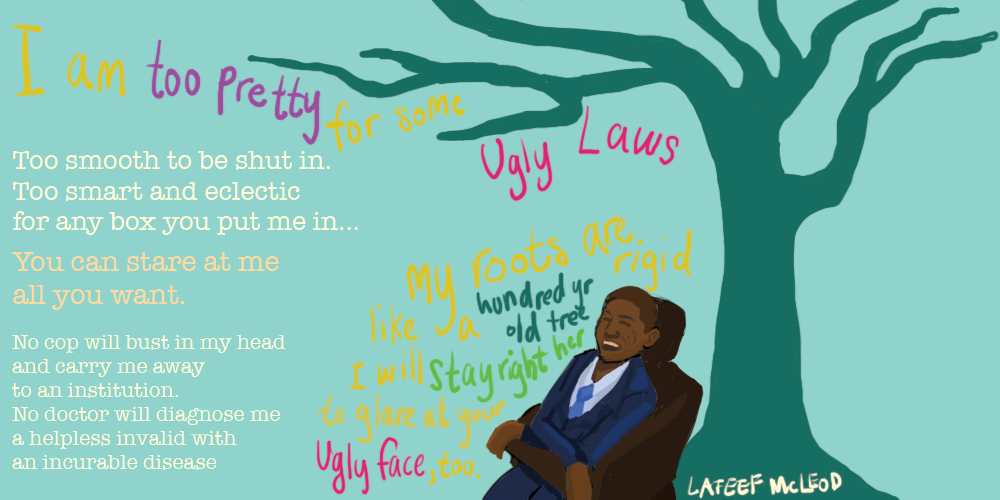

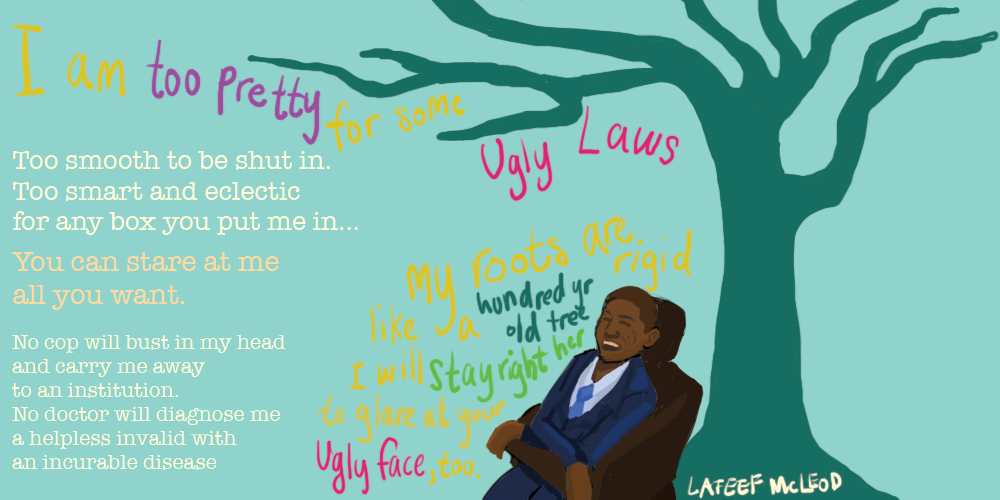

I am too pretty for Ugly Laws - Lateef McLeod

Brown, Keah. "Nurturing Black Disabled Joy." Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong, Vintage Books, 2020, pp. 117-120.

Image caption: A portrait of Keah Brown's face overlays a blue background. She is smiling and wearing blue frames. Above her green text reads "My joy is my freedom." Beside her is the hashtag "#DisabledAndCute," a viral hashtag she coined in 2017. Beside the hashtag is light blue text that reads "Deserve to be seen" and orange text that says "Living unapologetically." A text bubble on the right coming from Keah's mouth reads "I wanted to celebrate how I finally felt, in this black and disabled body, I , too, deserved joy" (Brown 118). To her left there is a yellow bubble with blue text inside that reads "the reality of disability and joy means accepting that not every day is good but every day has openings for small pockets of joy" with a literal green pocket containing a purple heart above the text (Brown 119).

In a gallery centering disabled voices, it's especially important to highlight Black disabled voices. Like almost all mainstream spheres of life in the U.S., the disability activist/organizer community, as Keah Brown also mentions, is incredibly white-dominated. Additionally, disability has historically been presented in the media as equivalent to suffering and being a worse alternative to death (ideas stemming from deeply-rooted eugenics ideology). I intentionally started the gallery with Keah's face and her piece on Black disabled joy to combat these two phenomena. Living and thriving have so many different meanings to disabled folks and mainstream media and the rest of society needs to understand and highlight these meanings and narratives instead of pushing the same, tired, ableist and unimaginative stereotypes of disabled folks.

Moore, Liz. "I'm Tired of Chasing a Cure." Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong, Vintage Books, 2020, pp. 75-81.

Image caption: A face is viewed from the bottom up - with the nostrils and chin visible but not the rest of the face. The background is orange and dotted with pink and red pills and light orange pill bottles. The face is cradled by two hands, and it is crying a stream of blue tears with the words "i'm tired" running down the face. Crowning the head is red spikes to represent headache/splitting pain. To the left, a blue speech bubble reads "Are you going to wish for a cure?". To the right, a bright green speech bubble reads "have you tried have you tried have you tried have you tried" to represent the onslaught of of advice from abled folks to 'cure' Liz's chronic illness/disability.

The art style is purposefully messy, scratchy and imprecise in this piece. I wanted to convey the rawness I felt in reading this narrative - the raw frustration of being constantly redirected to a new cure, constantly gaslighted by medical professionals after revealing inner struggles, and constantly receiving unwanted and unsolicited advice from abled people who act as if they not only know more, but also as if every trick in the oudated book hasn't already been tried. This piece is a self reflection and an introspection that lets Liz and the readers to slow down and ask themselves: What do they really want? Is it a cure to chronic illness and disability? Is it worth constantly striving for a kind of normalcy that they most likely will not return to? Out of all six pieces, this piece touches most directly on the way the medical model of disability can contribute to internalized ableism and limit the ways disabled and abled folks dream on how to 'better' their own lives. "There is a high cost to pursuing miracle cures," Liz notes, and it illustrates how unforgiving our current society is on disabled bodies and souls and also how unaccepting society is. Liz asks why we can't try acceptance - acceptance of "battered" and "broken" beings. Acceptance in the form of communal support and love. This is what is necessry to survive, because Liz knows that if she continues her pursuit to find cures to her connective tissue disorder and "achieve the person" she once was, she will miss the person she has become (Moore 81).

Sjunneson, Elsa. "How to Make a Paper Crane from Rage." Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong, Vintage Books, 2020, pp. 134-140.

Image caption: This is a step-by-step illustration of the literal and figurative steps to folding a paper crane of queer disabled rage. There is an audio description of the art above, read as a spoken word poem - unfortunately, I am currently still working on making this player keyboard accessible.

It's exhausting to even survive in spite of and against ableism. Queer disabled rage stems from a society that continually places expectations on queer disabled folks, expecting them to conform in order for society to see them as members of society. Social media has allowed the disability community to extend farther and connect with each other on a wider level, but at a cost: the rage, especially queer disabled rage, and other raw emotions that disabled activists, writers and people have can be more easily co-opted and used against them. In this piece, Elsa discusses how her rage has turned more strategic, utilizing her being vulnerable about her identity, background and struggles to "shift perception of disability," see disabled folks like Elsa as whole, and push for change (Sjunneson 139). Her writing is expertly crafted and purposeful, and she can take control of how she presents herself and how to use her voice. Elsa is by far not the only one who is an activist or advocate who expresses herself in this way. The rest of society's duty is to listen to the "radical vulnerability" and receive the paper cranes hiding the years of rage borne from ableism and painful events (137).

McLeod, Lateef. "I Am Too Pretty for Some 'Ugly Laws.'" 2018. Lateef.

Image caption: Lateef is wearing a blue suit and tie and is resting underneath a dark green tree with extended gnarled branches. In flowing text, the words "I am too pretty for some Ugly Laws" float above and underneath the branches. "too pretty" and "Ugly Laws" are in pink and red respectively while the rest of the words are in yellow. Typed, white-text snippets of his poem read below: "Too smooth to be shut in. Too smart and eclectic for any box you put me in...You can stare at me all you want. No cop will bust in my head and carry me away to an institution. No doctor will diagnose me a helpless invalid with an incurable disease." The last verse of his poem is handwritten in different colors: "My roots are like a hundred-year-old tree. I will stay right here to glare at your ugly face, too" (McLeod 226).

This is my favorite poem in this anthology. I absolutely love its confidence and refusal to back down in the face of ableism. "Ugly" policies and laws like Chicago's policy in 1967 that "any person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated...deformed so as ot be an unsightly or disgusting object...shall not theirein or thereon expose himself oto public view..." were meant to shame, dehumanize and further isolate disabled folks (McLeod 226). Despite structural and ideological attempts to shame disability perspectives away, Lateef holds his ground, firmly stating that his roots are "like a hundred-year-old tree" and that he will stay to glare at their ugly face (226). Reading words like these makes me even further convinced that disabled folks, especially QTPOC disabled folks, have and should be leading the forefront of the movement towards accessibility. The rest of society misses out on the sheer resilience disabled folks have (and I understand that this word holds mixed connotations for many - because it is the harmful ableist society that pushes people to be resilient in the first place).

Samuels, Ellen. "Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time." Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong, Vintage Books, 2020, pp. 189-196.

Image caption: The painting is split between the left and right. On the left side, the background includes both a shining yellow sun with a skyblue background and a moon with a dark blue sky and pouring rain. The green words "Listen to the" surround Ellen's figure. Ellen has her eyes closed and is hugging herself. On her body there are the pink words "body mind." The whole sentence reads "Listen to the body mind." Her torso hovers over a clock with the blue words "Take the time you need." Ellen is gripping the two red clock hands in her hand. On the right side is a representation of the current capitalist system that this piece indirectly critiques. The office buildings representing the dominating corporate culture have a human arm (the collective 'arms' of all the workers they exploit and the arms of CEOs and millionaires and billionaires) manipulating a pink clock shaped like a gear. This clock represents how time works in our ableist society. An email appears to "me" from "my boss" saying "Hey, I expected this 2 days ago. Where is it? Why are you taking so long?" Purple calendar sheets go by indicating the ableist passsage of time. Text messages in purple and green read "hey, you're late" and "expect this to dock your pay. next time, you're fired."

As someone who struggles with anxiety and with over-extending themselves, this piece was one of the most impactful pieces I read in the anthology and one of my favorites. In a world that constantly asks us to stay overtime, go above and beyond and work ourselves to the bone, reimagining how we can re-orient our lives around a different structure of time itself is revolutionary. This idea of 'crip time' and listening to your 'bodymind' in of itself is resistance and a clear example of why ANY kind of push towards social change should not only include but also be led by disabled folks. The experiences of nondisabled folks would not allow for dreaming of a radical concept like crip time, which encompasses self care, self love and being in tune with yourself before doing anything for anyone else. I cried a little in relief after reading this piece because it provided me an answer outside of the capitalist system to questions about 'work-life balance' and 'burnout' that really concerned more about self-care and being able to survive and thrive.

That being said, Ellen's piece on crip time isn't just about how society needs to reimagine time as a form of providing accessibility and fostering self-love and community sustainability. Crip time is "time travel," in how outwardly young bodies can have the "impairments of old age" (Samuels 190). Crip time is "grief time" and how time slows down when we lose loved ones and we enter a state of grief and have a strong desire to warp time to flit between the past and present (192). Crip time is "broken time" in its insistence for bodyminds to take breaks - which to me was the framing that left the deepest impression on me - and for us to stop pushing our bodies "away from us while also pushing [them] beyond [their] limits" (192). Crip time is "sick time," which never bodes well in our capitalist society when sick time means less opportunity for companies to profit and more opportunity to lose jobs (194). Crip time is "writing time" for Ellen and "vampire time" in the way bodyminds refuse to bend to the will of a scheduled, strict world. Crip time is a lifestyle. Nondisabled folks should listen to disabled folks on how to incorporate crip time into society to make our world more accessible and kind not only to each other but also ourselves.

smith, s.e. "The Beauty of Spaces Created for and by Disabled People." Disability Visibility, edited by Alice Wong, Vintage Books, 2020, pp. 271-275.

Image caption: There is a slanted aerial view of the stage of "Descent," a piece choreographed and performed by Alice Sheppard and Laurel Lawson. The two performers elegantly wheel around each other as hanging lights surround them. The stage is colored in dark blue and green swirls. Behind them rests a blue ramp. Music plays in the air - represented by colorful notes decorating the stage. The phrase "crip space" is written in light green on the stage. At a 90 degree angle on the front-facing portion of the stage, the phrase "space by us, for us" is written in light purple. An ASL interpreter stands in front of the stage, dressed in all black and signing. Three people sit at the front as they observe and marvel at the performance. All three are thinking the same thought: the bold yellow words "For ME." drift in a blue cloud.

For the millenia that disabled folks have been excluded from mainstream media and practically all spheres of abled society, it should not be surprising that there are disabled-centered spaces where folks have the ability to live and thrive as they are. I always try and remind myself how lucky I am to even be informed of organizations like Sins Invalid, take space in crip spaces and watch performances by and for the disabled community. I admire the way s.e. smith discusses the necessity of these spaces, stating how others taking offense at the existence of performance spaces like the one illustrated is why they're needed, because "as long as claiming our own ground is treated as an act of hostility, we need our ground" (smith 274). These spaces are respites from the soul-sucking, ableist society outside - this is illustrated at the end of smith's piece when they have to get back home via BART and the elevaors "are, as usual, out of order" (275). It's ridiculous to demand the non-existence and refusal to understand the necessity and empowerment performance spaces provide when disabled folks can barely use public goods and services.

When communities strive for cross-cultural unity and disability solidarity, how are they able to cultivate spaces where "everyone has that soaring sense of inclusion" and are able to have "difficult and meaningful conversations"? How are we able to do this? s.e. smith brings up these thought-provoking broad questions that should be considered when dreaming and building towards a kinder and more accessible world. One thing is certain: refusing to "consider the diversity of human experience" and promoting exclusion will only decrease accessibility (274).

All pieces from Disability Visibility impacted me in some profound way. There were people who I wanted to highlight but didn't have capacity or time to do so, such as Stacey Park Milbern, an incredible queer Korean disabled activist who passed away this year. Hearing her speak and looking through the hashtag #WhatStaceyTaughtMe made me emotional - not in the inspiration porn-esque way - because other than Stacey and a few other folks, I rarely see Korean and Korean diasporic representation as I dive into disability justice.

There were also pieces that I so desperately wanted to create art from and visualize somehow. Some that were so, so important to me and fit the theme of "dreaming of a kinder, more accessible world," however, didn't feel right creating art for. One of these pieces was Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha's piece "Still Dreaming Wild Disability Justice Dreams at the End of the World." Leah's work centers queer trans mixed-race and diasporic South Asians and Sri Lankan people of color and abuse survivors. The events she describes in her poem, "Psych Survivors Know," for the "people in the ICE concentration camps" deliver gritty, raw and real emotions and feelings that I don't believe art could convey any better. Organizing in the harshest conditions in settler-colonialist U.S. is extremely far from the traditional view of organizing. Inevitably, when I draw my interpretations of these stories that I as a reader have had the privilege of reading, I put my own inherently ableist spin on it. Even if I don't mean it, my own lived experiences will never do justice to the visions that disabled folks have for a world that truly meets their needs. Nevertheless, even if an artistic interpretation of Leah's piece isn't in the gallery, I consider hers the piece in Disability Visibility that talks the most about what a crip future looks like and how grassroots organizations are already building towards this future.

It's also incredibly important to mention that many of the concepts that narratives within Disability Visibility highlight, such as communal living, mutual aid and crip time, are not achievable in our current capitalist system that prioritizes output and profit over people. Ableism has existed much longer than capitalism, but capitalism continues to perpetuate ableism. It is not a coincidence whatsoever that many disability justice groups incorporate abolition into their community care and organizing work. This is more of a personal take, but the more I learn about disability justice, the more I realize that policies that would be labeled by some as "radical" are not so radical when they are the ones meeting the needs of folks with various disabilities.

made with love by kwon.js